For many decades the noseband was of no particular interest to the world wide equestrian press, but over the past years this piece of leather on a horse’s bridle has made it into the headlines, unfortunately, for unpleasant reasons. Often too tightly cranked in dressage or too deeply dropped in pony classes, the noseband has been wrongly used either to hide training issues or out of ignorance.

This raises the justified question whether it is useful that a steward checks the correct fitting of a noseband only after a CDI class is finished instead of before the ride. The International Society of Equitation Science (ISES) has brought the wrong use of nosebands into the open on a scientific level. While it regretfully casts a negative shadow over the use of noseband it quite rightly, points out that severely tightened nosebands are an indicator of wrong developments in dressage even at high performance level.

Nosebands, the Centre of the Attention

In the interest of the welfare of the horse it is important that wrong and abusive use of the noseband should be brought to light. Eurodressage’s chief editor Astrid Appels already wrote on the problem in her much noticed editorial “A slip of the tongue” in June 2011. While critical minds caring for the horse are appreciated, there are also even more fanatical voices out there who condemn any use of a noseband and consider it cruelty towards the four-legged partner even to put one on. They simplify and solve the issue by claiming that riding without a noseband is the best to reveal which top riders have a light and ideal contact and which not.

Like all things in the world there is much grey area in between the black and white. The same is valid for the noseband. For this "Noseband Special" we are tackling the topic of the noseband from different perspectives and instead of focusing mainly on what a noseband can do for a horse, we will also look into its origins, history and evolution and in which ways it can be useful in the training of a dressage horse.

History: The Evolution of the Noseband

It is said that long before humans put the first bits made of wood or iron into a horse's mouth they used the sensitivity of the nasal bone to tame the strong animals. About 7000 years before Christ carriage drivers used a noseband similar to the dropped one which was positioned that deeply that it pressed into the nostrils if the reins were pulled and thereby hindered the poor horse from breathing. It is reported they stopped the horses that way. On sculptures from Persia 1000 years later horses were shown “on the bit” for the first time with a round topline and the head at the vertical. Because the horses used at that time were heavy bodied stallions and the curb bit was still not invented experts assume that the noseband on the sculptures had been barbed inside to control the power of the horse and bring its head down.

It is said that long before humans put the first bits made of wood or iron into a horse's mouth they used the sensitivity of the nasal bone to tame the strong animals. About 7000 years before Christ carriage drivers used a noseband similar to the dropped one which was positioned that deeply that it pressed into the nostrils if the reins were pulled and thereby hindered the poor horse from breathing. It is reported they stopped the horses that way. On sculptures from Persia 1000 years later horses were shown “on the bit” for the first time with a round topline and the head at the vertical. Because the horses used at that time were heavy bodied stallions and the curb bit was still not invented experts assume that the noseband on the sculptures had been barbed inside to control the power of the horse and bring its head down.

In the 16th century when Italy became famous as the centre of art the horses painted at the time were still the heavy type for which man needed much strength to collect them, even though the curb had been invented and fine tuned for long. Sharp curb bits and the “careta”, a barbed noseband with reins attached, held the horses together. The noseband wasn’t always barbed, sometimes it was only a plain flat leather noseband. It is said that the famous Grisone used a kind of noseband called “capezona” to which reins were attached and which tightened when the reins were taken.

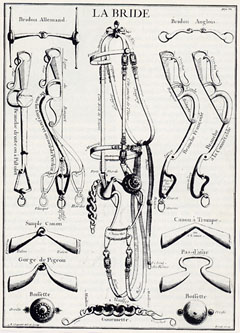

The noseband as we know it nowadays is a rather young piece of tack, originally evolved from the cavesson we still see today in lunging, hand work or even in riding. The most simple noseband for sure is the one we can see in Francois Robichon de la Guérinière’s legendary manual “Ecole de Cavalerie” (“Reitkunst”), but it could be seen on even earlier historical paintings. It is a simple thin and flat piece of leather pulled on each side through the lower parts of the cheek pieces. De la Guérinière didn’t mention anything on this noseband, nor on its construction nor on its aim. Instead he explained quite detailed how a rider can find the appropriate bit by writing how the different bits work and fit in different mouths.

The noseband as we know it nowadays is a rather young piece of tack, originally evolved from the cavesson we still see today in lunging, hand work or even in riding. The most simple noseband for sure is the one we can see in Francois Robichon de la Guérinière’s legendary manual “Ecole de Cavalerie” (“Reitkunst”), but it could be seen on even earlier historical paintings. It is a simple thin and flat piece of leather pulled on each side through the lower parts of the cheek pieces. De la Guérinière didn’t mention anything on this noseband, nor on its construction nor on its aim. Instead he explained quite detailed how a rider can find the appropriate bit by writing how the different bits work and fit in different mouths.

He didn’t spend a word on the shown noseband because it didn’t seem to be of any importance for the art of riding he practised and it was little more than decorative. Instead de la Guérinière pointed out that most important to riding are the hands and the judgement of a rider. Without these requirements the best bridle would remain useless. These are wise words which have changed in truth in our days. This simple noseband printed in “Ecole de Cavalerie” can still be seen, for example in bridles used in show classes or on stallions bridles. Its purpose is still nothing but decoration.

The Dropped Noseband Set the Standard

The noseband which soon after its invention began to dominate until the 1970s was the dropped noseband or how the Germans call it, the “Hanoverian noseband”.

It was invented in the 19th century by Ernst Friedrich Seidler, a German trainer who worked at the Spanish Riding School in Vienna under the tutelage of legendary chief rider Maximilian von Weyrother. Based on the traditional cavesson he developed the dropped noseband which is named after Germany’s great cavalry school of Hanover where Seidler worked as well. Although not easy to fit correctly on all horses this noseband was the most common for snaffle bridles for many decades and got established as a traditional part of the tack used at the Spanish Riding School in Vienna. The dropped noseband appears in the exhibitions during which the horses are worked in hand or in long reins or with the young stallions when they are presented in a snaffle bridle. Also at the Royal Andalusian School in Jerez de la Fronteira and at the Portugese School of the Art of Riding in Lisbon the dropped noseband is still in regular use when the horses are ridden in the snaffle bridle or worked in hand.

It was invented in the 19th century by Ernst Friedrich Seidler, a German trainer who worked at the Spanish Riding School in Vienna under the tutelage of legendary chief rider Maximilian von Weyrother. Based on the traditional cavesson he developed the dropped noseband which is named after Germany’s great cavalry school of Hanover where Seidler worked as well. Although not easy to fit correctly on all horses this noseband was the most common for snaffle bridles for many decades and got established as a traditional part of the tack used at the Spanish Riding School in Vienna. The dropped noseband appears in the exhibitions during which the horses are worked in hand or in long reins or with the young stallions when they are presented in a snaffle bridle. Also at the Royal Andalusian School in Jerez de la Fronteira and at the Portugese School of the Art of Riding in Lisbon the dropped noseband is still in regular use when the horses are ridden in the snaffle bridle or worked in hand.

The flash noseband (also called “Aachen noseband” ) which is without a doubt the most popular among dressage riders today emerged comparatively late. The exact date of invention nor the inventor are known but it was about in the late 1960s when it increasingly appeared on the jumping scene for which it was originally made to keep the horses mouth more effectively shut. It also served as aid to attach a standing martingal to the cavesson, something not allowed in jumping competitions anymore. From the jumping camp it transferred to dressage in the 1980s and now has by far overtaken the dropped noseband which was so common among dressage riders of all decades before.

The grackle, figure eight or as the Germans say “Mexican” noseband was named after the horse Grakle that won the British Grand National in 1931 wearing this noseband. It was first seen in jumping on the horses of the successful Mexican jumping team of the late 1940s and it is still quite popular among jumping and eventing riders. This noseband has never really spread within dressage, though it is occasionally seen in training sessions.

The Mystery Use of a Noseband

Nowadays many magazines throughout the world repeatedly publish journals in which the different nosebands are shown and their function and fitting explained, but the major literary handbooks of the “old masters” fail to go in-depth on the matter. Either because there were more or less only two nosebands around -- the dropped and the English -- or it was just natural that every bridle was fitted with a noseband and there were no such discussion of “with or without” or “which” like nowadays.

One of Germany’s most popular riding manuals, Wilhelm Müseler’s “Reitlehre”, first published in the 1930s and still in print, explains that nosebands are there to hold the bit straight and quiet and to prevent that the horse opens its mouth and thereby avoids the impact of the reins. He enumerated the most common nosebands, but didn’t mention a word about how they should be fitted or how differently they work on a horse. Did Müseler assume when he wrote his book about 80 years ago that his readers were competent enough to know the use and fitting themselves?

Richard Wätjen, an accomplished German dressage rider and trainer round World War II, distinguished in his manual “Das Dressurreiten” that the correctly fitted bridle is most important if one wants to advance his horse in dressage. He recommended to attach a noseband to every bridle and, judged by the description he gave, he was referring to dropped noseband. For him the aim of a noseband was to make it impossible for the horse to open the mouth, but he warned the readers only to tighten the noseband so much as the horse could still chew.

Richard Wätjen, an accomplished German dressage rider and trainer round World War II, distinguished in his manual “Das Dressurreiten” that the correctly fitted bridle is most important if one wants to advance his horse in dressage. He recommended to attach a noseband to every bridle and, judged by the description he gave, he was referring to dropped noseband. For him the aim of a noseband was to make it impossible for the horse to open the mouth, but he warned the readers only to tighten the noseband so much as the horse could still chew.

While these and other old manuals like those of Bürkner, Podhajsky, Steinbrecht, Seunig, Decarpentry or Bürger never really go out of fashion and are all still in print today, there are more recent manuals on the market which became quite popular as well.

In British Olympic dressage rider Jennie Loriston- Clarke’s book “The Complete Guide to Dressage” which was first published in 1987 the author mentioned the flash and the dropped noseband. Loriston-Clarke stressed the ability of the flash to hold the bit straight and advised the reader to pay detailed attention to the correct fitting of the dropped noseband. Loriston-Clarke warned that if the upper part of the noseband is too long it interferes with the bit and applies a constant pressure and this could lead to a tongue problem. With a young horse being broken in the now well known FEI judge recommended using a cavesson instead of a noseband at the beginning.

Surprisingly one of the most popular manuals of the past few years, “Dressurreiten” by multiple Olympian Kyra Kyrklund and Olympic judge Jytte Lemkow, doesn’t mention the topic of nosebands at all.

-- by Silke Rottermann for Eurodressage.com

Part II: Noseband Special: Part II: The Purpose of a Noseband

Related Link

ISES Suggest to Empower FEI Stewards to Control Tightness of Noseband