It seems impossible to imagine that in the early 1960s a Canadian pony clubber of barely 14 had set the target to compete her young and difficult thoroughbred off the racetrack in the dressage Olympics in 1964 in Japan, a country without a dressage tradition back then.

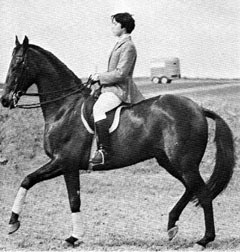

It was no day dreaming and it became reality thanks to inconceivable efforts from the determined girl and her faithful horse. We talk about Canada’s 7-times Olympian Christilot Boylen and her first dressage horse Bonheur xx, whose story is still one of the most inspirational in the sport.

In 1960 Christilot was 13 years old and a member of the Toronto and North York Pony Club, one of countless riders who acquired the necessary skills through this popular institution which still exists in several countries. Horse shows, hunter trials, jumping and eventing competitions appealed the most to the young boys and girls and Christilot’s parents were looking for a suitable horse for her daughter when the offer came to look at a young thoroughbred.

The 5-year old, which came off the racetrack after two unsuccessful seasons, was owned by one of Canada’s equestrian heroes, Brian Herbinson, who was on the young bronze medal winning eventing team at the 1956 Olympics in Stockholm. Being the typical representative of the noble American thoroughbred with a shining dark brown coat Bonheur, of course, attracted Christilot who loved the gelding’s soft movements. So her parents bought the horse then called Colonel xx (being sired by Colonel O ‘F out of Miss Wezie by Boswell) for the moderate price of 800 Canadian dollars.

Which young horsey girl hasn’t dreamt of owning a “black beauty”? But Bonheur xx, renamed by Christilot, wasn’t only beautiful, he was a young thoroughbred of high spirits and quite a handful for a 13-year old girl. Although thoroughbreds can be wonderful horses for many purposes a young one off the racetrack may not be the best choice for an inexperienced pony clubber.

Christilot did not mind too much the escapades of Bonheur because she loved him the way teenagers do: he was her very own horse which she cared for day by day.

Their affection for each other was soon shown the fact that Bonheur was deadly jealous when Christilot paid attention to another horse than him. In the pony club several thought he was far too difficult to handle by the teenager and so did Christilot’s caring mother, a renowned dancing instructor, with no real experience in horses. An agreement was made to keep the horse, but that Christilot was only allowed to ride him under skilled tutelage.

Their affection for each other was soon shown the fact that Bonheur was deadly jealous when Christilot paid attention to another horse than him. In the pony club several thought he was far too difficult to handle by the teenager and so did Christilot’s caring mother, a renowned dancing instructor, with no real experience in horses. An agreement was made to keep the horse, but that Christilot was only allowed to ride him under skilled tutelage.

By coincidence Christilot’s mum found out that a certain General von Oppeln- Bronikowski was near their home at Oak Ridges and should have been a famous dressage rider before World War II. Actually Hermann von Oppeln-Bronikowski had been on the gold medal winning German dressage team at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin on the 17 years old Trakehner Gimpel as member of the famous Cavalry School of Hanover.

The General agreed to take a look at Christilot and Bonheur xx and his positive impression led to the decision to teach the young pair during his stay in Canada. It is allowed to doubt that many teenagers would have stood the General’s strict training regime, but Christilot and her young horse really profited from the his unmerciful approach to training.

When the General left Canada Christilot was sent to the recently founded Canadian Olympic Equestrian Centre at Newmarket which was run by the great Anatole Pieregorodzki, a native Pole who had led the Canadian eventing team to its unexpected Olympic bronze medal some years earlier. There Bonheur did all kind of activities, he was hacked regularly, show jumped and taken cross country.

When the General left Canada Christilot was sent to the recently founded Canadian Olympic Equestrian Centre at Newmarket which was run by the great Anatole Pieregorodzki, a native Pole who had led the Canadian eventing team to its unexpected Olympic bronze medal some years earlier. There Bonheur did all kind of activities, he was hacked regularly, show jumped and taken cross country.

Though both did it with much engagement and took it seriously, Christilot’s much admired trainer Anatole foresaw their destiny in another equestrian field: dressage. He told the young girl that their aim should be the dressage competitions of the 1964 Olympic Games in Japan.

Christilot admitted to Eurodressage that Bonheur wasn’t a very good jumper since he always hung his legs and dressage seemed a discipline where an elegant thoroughbred could do best.

But once again dark clouds hung over the young partnership. Anatole suffered a heart attack while walking a self-designed cross country course with his pupils and he died not long after. So Christilot and Bonheur xx found themselves without a proper trainer in Canada.

When the General was back in Canada for a short period of time Bonheur’s future was discussed among him and Christilot’s parents. Much to their regret the General couldn’t assure them that Bonheur would be a proper horse to reach Grand Prix dressage level one day. His main doubts were not on the horse’s quality but on his constitution. Bonheur was a rather petite looking thoroughbred and it was questioned if he would stand the hard training necessary to reach the highest levels.

The Hanson family decided to sell him and buy Christilot a more proper horse in Europe to fulfil her aim of becoming an Olympic dressage rider.A man from the USA agreed to buy him, but luckily he had to cancel the sale and Bonheur remained Christilot’s horse—this time forever. Future plans were made to secure the pair’s further development and the General agreed to take Bonheur and Christilot under his tutelage in Germany for a certain period of time.

So in the winter of 1961 the sensitive Bonheur flew for the first time in his life, something that worried his owner. Transporting horses by plane is common today with special containers and airplanes. But back in the 1960s it was much more an adventure and a high risk. In the 1960s quite a few Olympic horses lost their lives on flights, being shot for panicking on the plane.

So in the winter of 1961 the sensitive Bonheur flew for the first time in his life, something that worried his owner. Transporting horses by plane is common today with special containers and airplanes. But back in the 1960s it was much more an adventure and a high risk. In the 1960s quite a few Olympic horses lost their lives on flights, being shot for panicking on the plane.

But “Bonny” survived unscathed and was stabled at the Hanover racetrack where the General was based. The following months became hard ones for horse and rider. Christilot, was barely 15 and for the first time away from home, living with a German host family. For long months she had to get up early in the morning and cycle long miles in all weather conditions to the stable. Every morning at 8 she had to be in the indoor arena to get the General’s strict training. First she had to face several lunging sessions to improve her seat until she rode the inside parts of her thighs bloody. Then the General worked on the improvement of Bonheur, transforming him into a dressage horse schooling at medium level in the months to come until the summer of 1962.

It was a hard thing because neither Christilot nor Bonheur had ever exercised shoulder-ins, half passes, pirouettes and flying changes. It was far from being the usual game of an experienced dressage horse teaching the young rider or the experienced rider training a green horse. Both youngsters had to learn the ropes together and both had to be most determined and passionate to bear it. Though it might be a very difficult time Christilot is grateful because she learned to take in criticism without complaining.

All the work paid dividends and in the summer of 1962 Christilot was able to ride her thoroughbred in her first dressage show ever at a small German shown in May.

Bonheur neither disappointed his rider nor his trainer. He won his first dressage competition ever and placed 3rd in a more difficult one later. At the end of June 1962 both flew home to Montréal and though having learnt a great deal during their stay at Hanover Christilot was convinced she would never gone through it all without Bonheur at her side.

Back in Canada at the Equestrian Centre in Newmarket Christilot had to work on her own. Bonheur, now being a dressage horse, was no longer jumped: “I stopped jumping him. He was not a good jumper and there was too much of an injury factor. But I hacked him a lot and we enjoyed swimming in a lake near our house.” In October 1962 they traveled to Washington D.C. to face the best riders on the North American continent in their first international show.

Special permission from the organisers had to be given as Christilot was only 15 and not allowed to start in senior competitions. Bonheur performed very well and placed 2nd in the Prix St. Georges behind a US Olympic dressage rider, so their first international show turned out to be a great success. Just a month later they became the Canadian Reserve Champions at the famous Royal Winter Fair Horse Show in Toronto. Of course it was encouraging, but Bonheur still was not a Grand Prix horse and had little time to move up the levels before 1964. One might ask what made Christilot so sure she had a chance to represent her country knowing her horse had to be ready fin two years.

Special permission from the organisers had to be given as Christilot was only 15 and not allowed to start in senior competitions. Bonheur performed very well and placed 2nd in the Prix St. Georges behind a US Olympic dressage rider, so their first international show turned out to be a great success. Just a month later they became the Canadian Reserve Champions at the famous Royal Winter Fair Horse Show in Toronto. Of course it was encouraging, but Bonheur still was not a Grand Prix horse and had little time to move up the levels before 1964. One might ask what made Christilot so sure she had a chance to represent her country knowing her horse had to be ready fin two years.

Canada unlike today had a very small dressage scene in the 1960s. Only in 1956 the country produced its first ever dressage Olympian -- Leonard Lafond -- who did quite well on an Irish thoroughbred called Rath Patrick xx. This talented horse later won the Aachen Grand Prix with the US rider Patricia Galvin and represented the US on two more Olympic Games.

So chances to be selected were comparatively high then.

Christilot continued her success with Bonheur in 1963 at PSG level, winning the US Horse Shows Association Dressage Medal Class in Washington D.C. and she became the Canadian Champion at the Royal Winter Fair.

It all looked promising, but to make the transition from Prix St. Georges to Grand Prix was such a big and demanding step which many horses are never able to make. Once a famous German dressage trainer stated: “Between a St. Georges and the Grand Prix are the Alps” and nothing is more true. To be selected for the Olympics Christilot just seemed to be too young and too inexperienced so the requirement was set by the Canadian Federation that she had to score 55% or more in a CDI prior to the Olympics.

Unfortunately General von Oppeln-Bronikowski couldn’t help Christilot as he had to work in the USA in 1964. So Christilot’s mother sent her daughter to the famous Reitinstitut von Neindorff in Karlsruhe, south Germany. The master agreed to take her and once again Bonheur had to cross the Atlantic.

Though the dark bay had traveled a lot in the meantime, it didn’t help Christilot to feel good about the strenuous journey that lay ahead. She reminisced: “Bonheur was not a great traveler and could never be tied up, he reacted totally claustrophobic.” She and Bonheur flew from Kennedy International Airport in the US to Amsterdam and from there to Stuttgart where both were collected by Mr. von Neindorff .

Only seven months remained to train Bonheur to Grand Prix. He had already started schooling the passage with the General, but hadn’t done a step of piaffe or flying changes every single stride. Furthermore, Christilot had never ridden these exercises before. Egon von Neindorff had established an institute for classical riding in the tradition of the Spanish Riding School and had highly trained dressage horses as schoolmasters for his students until his death in 2004. Already in the 1960s Egon was a renowned trainer (as a student of Felix Bürkner). In that era Van Neindorff had coached legends such as Richard Wätjen or Otto Lörke. Bonheur and Christilot profited a lot in the months to come.

Only seven months remained to train Bonheur to Grand Prix. He had already started schooling the passage with the General, but hadn’t done a step of piaffe or flying changes every single stride. Furthermore, Christilot had never ridden these exercises before. Egon von Neindorff had established an institute for classical riding in the tradition of the Spanish Riding School and had highly trained dressage horses as schoolmasters for his students until his death in 2004. Already in the 1960s Egon was a renowned trainer (as a student of Felix Bürkner). In that era Van Neindorff had coached legends such as Richard Wätjen or Otto Lörke. Bonheur and Christilot profited a lot in the months to come.

Christilot, once again living at a host family, went through several working sessions a day. From the inevitable lunging sessions to improve her seat to lessons on von Neindorff’s horses and of course sessions with Bonheur.

Bonheur’s most demanding task was to learn the piaffe which many thoroughbreds find difficult. Von Neindorff worked him in all possible ways: in long reins, in hand and under the saddle. One may assume it must have been a very forced training since there was so little time, but Christilot denies that: “Neindorff’s method of doing short stints more often prevented too much stress. His motto was ‘classical training has no timetable’”.

Nevertheless it was hard work and as Bonheur was a nervous, eccentric horse Christilot did all she could to settle his nerves and keep him happy. She added long walks, grazing and regular massages to loosen his hard working muscles to the serious training. Luckily Bonheur's perseverance pulled him through on his way to Grand Prix level: "he would never quit, even when he was sick.”

In the summer of 1964 Bonheur was able to show all the Grand Prix exercises and though von Neindorff wasn’t very happy to interrupt the meticulous preparation Christilot had to go to a show in order to get the required 55%.

She was invited to compete at the famous CDI Rotterdam in August and again was given special permission to start despite her too young age according to international rules. Although Christilot had to face some bad luck (Bonheur hit his hip while rolling in his stable and was a bit stiff) she was able to score over 55% and placed 7th.

Bonheur finally left Karlsruhe and flew from Stuttgart to Tokyo at the end of September, a mere month before the Olympic Grand Prix. Christilot was then just 17 year olds. He survived the long flight and gruesome drive from the Japanese airport to the Equestrian Centre 150 km outside Tokyo and was stabled with the German and Russian dressage horses.

Without a trainer and a peer as groom at her side Christilot drew a lot of attention from the other competitors. After some days of quiet hacking around to let Bonheur recover from his exhausting journey, Christilot began training him twelve days prior to the Grand Prix according to a plan made by Mr. von Neindorff

.

Soon she found herself in the huge indoor arena observed by Russians, especially by the reigning Olympic Champion Sergej Filatov. Though not speaking English he helped her a bit with Bonheur and showed serious interest in her beautiful horse. “I was over my head in Tokyo, but I was there and I learned a lot,” Christilot reminisced.

When the day came that Christilot had to enter the arena as the 8th starter in the Olympic Grand Prix, the moment she and her faithful horse had worked so hard for over the past years was there. Though Bonheur detested the deep footing, they showed a nice ride. Bonheur’s great strength was “a canter to die for” and the overall picture of elegance caught many in the audience. In the end Bonheur quite logically hadn’t won a medal, but set a record of his own by carrying the youngest Olympic dressage rider ever. Christilot’s unique achievement to compete in Olympic Games at the age of 17 was only outdone in 2008 when a Brasilian dressage girl of 16 competed in Hongkong, repeating what a Columbian dressage rider had done in 1988.

When asked what impact her Olympic appearance had in Canada Christilot answered, “a very small one, but we had a small energetic group.”

After the Olympics Bonheur returned to Canada with his mistress. Both took part in several clinics of different trainers visiting Canada and finally started to train with the great Willi Schultheis. With the time Bonheur became more and more experienced at Grand Prix level and at his achilles’ heel, the piaffe, though “footing was always a factor, a deep ground was very difficult for him.”

Christilot was able to win the then renowned Colonel Kitts Memorial Trophy (named after a famous Olympic dressage rider of the US) in Detroit after winning the Grand Prix there three times in a row: “Aside from the Olympic starts this was Bonheur’s career highlight.”

In 1967 the Pan American Games were held on home turf in Winnipeg and Bonheur contributed to the Canadian team’s bronze medal behind Chile and the US to win his longed international medal, Christilot’s first of many to follow at Pan American Games. “It was a racetrack setting, unfortunately for me and Bonheur”, Christilot confessed, “at such a venue he got even more exited.” A year later he flew to Mexico- City to attend in his second Olympic Games, this time as part of a Canadian team. More matured and experienced he placed a respectable19th and the team came 7th.

In 1967 the Pan American Games were held on home turf in Winnipeg and Bonheur contributed to the Canadian team’s bronze medal behind Chile and the US to win his longed international medal, Christilot’s first of many to follow at Pan American Games. “It was a racetrack setting, unfortunately for me and Bonheur”, Christilot confessed, “at such a venue he got even more exited.” A year later he flew to Mexico- City to attend in his second Olympic Games, this time as part of a Canadian team. More matured and experienced he placed a respectable19th and the team came 7th.

After many exciting years in which Christilot learned together with her horse all the time Bonheur had to be retired because he wasn’t sound enough anymore. “I retired him and turned him out, but he was furious about it for three months! He attacked every horse he could. We finally found a brood mare he liked to be with”. Asked if there was one special experience with Bonheur in their years together Christilot stressed: “There was not one special experience. This horse was an experience in itself! The lessons I learned from him have helped me through my whole career.”

Bonheur lived a long happy retirement in Canada and had to be put down in 1979 after he suffered a colic and didn’t manage to get back to normal. He was inducted in the Toronto Cadora Hall of Fame in 2009.

One must suppose that after all Bonheur and Christilot went through he must have been the horse with whom she had the strongest bond. But Christilot surprisingly denies it: “No, interestingly I usually have very strong bonds with all my top horses. I want to know them inside out even though I am a professional. I suffered the losses of my horses through sale, illness or death. One learns to be a philosopher in this sport and when working with animals. You accompany them and they accompany you for a period in your life.”

Bonheur was the horse that accompanied Christilot through her teenage years, her first years as an international dressage rider (who went on to do 7 Olympic Games so far) and he was “her first friend and teacher. To Bonheur I will always be very grateful.”

Article by Silke Rottermann (as told by Christilot Boylen)

Recommended reading

- Christilot Boylen, Canadian Entry, published by Clarke, Irwin & Company Limited, Toronto 1966 (out of print, available second hand).

Relate Links

Dutch Courage, Pioneer of British Dressage

Pepel, a True Legend of Russian Dressage